Asked about her reaction to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022 eliminating the federal constitutional right to abortion, Catherine Cansino, MD, replied, “There’s a lot of fear.”

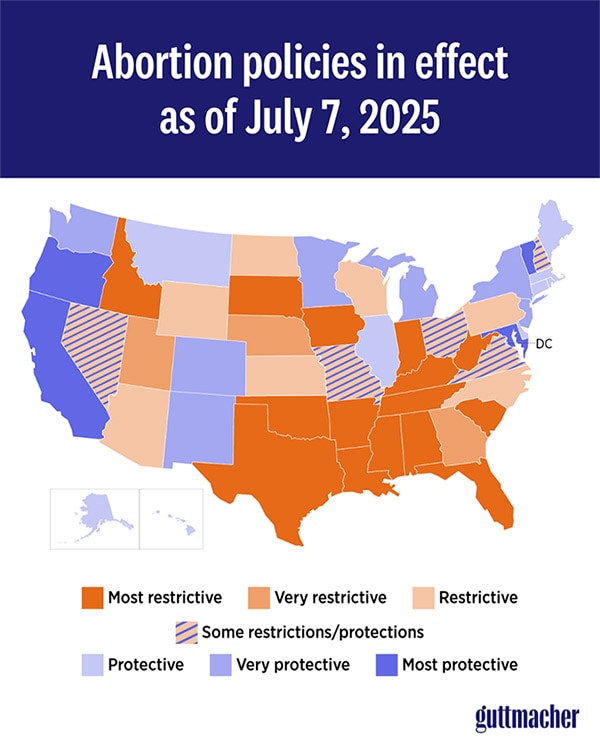

In the resulting fallout from the Dobbs decision, 41 states now ban abortion altogether or at varying gestational ages and with varying exceptions. If a patient is having a miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy, they may wonder whether the treatment is considered an abortion, said Cansino, an obstetrician at an academic center in California.

For providers, the question is, “Even if you are doing the right thing, will something bad happen?” she said. Abortions are legal where she practices, but she often wonders whether there will be legal ramification for caring for out-of-state residents.

Despite the increased stress experienced by abortion providers, many are still finding ways to meet demand for vital reproductive health services in the wake of the Dobbs decision. Some, however, are adapting in ways that may reduce the availability of obstetrical care — and healthcare in general — in parts of the US with strict abortion laws.

The Dobbs decision has begun to affect the obstetrical workforce in parts of the US. In a recent research letter published in JAMA, Dana Howard, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Bioethics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, looked at how Dobbs may have influenced where abortion care providers practice. She and her colleagues surveyed a wide range of clinicians (physicians, advanced practice providers, clinicians, and nurses) who provided abortion care about their practice location the year before Dobbs and again at the time of the survey in 2023.

Sixteen percent of the respondents had relocated to a new state to practice: 42% of those previously practicing in a state with an abortion ban had moved to one without a ban compared with only 9% of clinicians from states without bans. “We were just struck by the difference between clinicians practicing in states that didn’t ban abortions vs states that did impose either a full ban or a 6-week ban,” said Howard. “They’re making these changes right now, but in 5-10 years these changes can have much larger effects on the Ob/Gyn workforce that we can’t measure yet.”

Another clear indicator of the negative impact of Dobbs on the Ob/Gyn workforce is the number of US medical school graduates applying to Ob/Gyn residencies in states with abortion bans. The most recent data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) from the 2023-2024 residency match reported a 6.7% drop in applications to programs in states with bans compared with a 0.4% increase in applications to programs in states where abortion was legal.

But access to training in abortion care had started to decline before Dobbs. In a 1991-1992 survey of program directors of Ob/Gyn residency programs in the US, the proportion of programs providing routine training in first-trimester abortion was 12% and for second-trimester abortion was 7%. Most of the programs that provided routine training continued to offer optional training, but residents in those programs were less likely to receive training in abortion procedures.

In response to these findings, in 1996 the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education implemented a requirement that mandated access to experience with induced abortion as part of residency education, although programs or residents with religious or moral objections could opt out. If residency programs did not have routine training available at their institution, they were expected to support residents in finding training options.

In 1999, the Kenneth Ryan Jr Residency Training Program was launched at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California San Francisco. “The Ryan Program was founded with the purpose of supporting Ob/Gyn departments to integrate abortion care and improve their training, and part of that includes also improving the care they provide for people with pregnancy loss,” said Jody Steinauer, MD, PhD, a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California San Francisco who currently serves as the center’s director.

Since its inception, the Ryan Program has supported 120 Ob/Gyn departments in improving their capacity to provide training in abortion procedures to their residents. In addition to learning the critical skill of safely evacuating the uterus, Steinauer stressed the importance of additional skills learned by residents at Ryan Programs that go along with learning abortion procedures. “You learn incredible skills in ultrasound and patient counseling, how to be empathetic and compassionate, how to do the actual procedure, anesthesia, and how to take care of people after their abortion,” said Steinauer. “It’s just critical to make our next generation really ready to not just provide abortion care, but really just compassionate care in lots of different areas of gynecology and obstetrics.”

Despite these successes, the passage of State Bill 8 in Texas prohibiting and criminalizing abortion, followed by the Dobbs decision, posed new challenges. According to Steinauer, there are more than 50 Ob/Gyn programs with over 1000 residents in states with bans. “Even if you’re only having a rotation for them in one of their 4 years, that’s still 250 Ob/Gyns residents each year that need training,” said Steinauer. “So we still have a long way to go.”

Rachel Crebessa, MD, whose residency program in a southern state did not offer abortion training even pre-Dobbs, described her struggles to find a place to develop competency in abortion procedures. “I reached out to no less than 50 different clinics or programs to try and find somewhere that had room and the capacity to take an out-of-state resident. I was met with a dead end every single time,” she said.

Fortunately, for residents in Crebessa’s position, the Ryan Program based at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in Portland, Oregon, immediately responded to the need to provide training to out-of-state residents. “When the leaked SCOTUS decision came out, we saw the writing on the wall,” said Alyssa Colwill, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at OHSU. “Not only were patients going to have restricted access to abortion care, but a large proportion of residents are training in states that were no longer going to be able to access abortion training.”

Colwill and her colleagues developed the Complex Family Planning Visiting Resident Elective, which is committed to educating out-of-state Ob/Gyn residents without access to abortion training in their home state. As of June 2025, the OHSU elective hosted 22 residents from 17 programs as well as three out-of-state fellows. “Residents have left this experience knowing that this is essential, routine healthcare, and without this training, they felt like there was a hole in their education,” explained Colwill.

Crebessa participated in the OHSU elective in the fall of 2023. For her, practicing in a state without an abortion ban was a relief. “There is no reason for me to be ashamed of the care that I was providing there [in Oregon] because it was the right thing to do,” she said. “I was definitely a lot more confident and open about the kind of care that I wanted to provide.”

The Guttmacher Institute reported that 1,037,000 abortions were performed in the US in 2023, the first full calendar year after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. This number represented an 11% increase from 2020, the last year in which formal estimates are available. Much of the increase was due to increases in states without bans that border states with bans, which saw a 38% increase in the number of abortions between 2020 and 2023. According to the most recent analysis of Society of Family Planning’s WeCount data, another driver is an increasing reliance on telehealth: In the last quarter of 2024, telehealth abortions accounted for 25% of abortions in the US compared with April-June of 2022, when telehealth abortions accounted for just 5%.

Although these numbers suggest that efforts by organizations such as the Ryan Program and the OHSU elective can help mitigate the effect of Dobbs, the geography of abortion availability is still daunting. OHSU’s Colwill said that Oregon has seen increases in patients from neighboring states seeking abortion services and she worries about the growth of maternity care deserts in other parts of the country. “We’ve seen in states like Idaho a large exodus of Ob/Gyns practicing in that state,” she said. “And since the Dobbs decision, they have closed two labor and delivery units in the state.”

Steinauer pointed out that AAMC also reported decreases in applications to residencies in other specialties in states that have abortion bans. Family medicine, pediatrics, internal medicine, and emergency medicine residency programs all saw declines in applicants in the 2023-2024 match. “I’m very worried that we’re going to see programs that don’t fill, until there are cities and regions in rural areas that don’t have enough doctors who can provide care in general,” she said.

But not everyone leaves. “There’s always that pressure of wanting to be close to family, but also there’s an internal drive of not wanting to be another statistic of somebody leaving a state just because it’s hard,” said Jewel Brown, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at an academic medical center in Florida. She attended medical school and completed her Ob/Gyn residency in Florida in the pre-Dobbs era, when her home state allowed abortions up until 24 weeks gestational age.

Brown chose to do a complex family planning fellowship in California as there wasn’t one in Florida. She dreamed of coming back to work with her former residency mentor to start the first complex family planning fellowship in Florida.

Initially, the passage of Dobbs seemed to deny that goal, but after finishing her fellowship in the summer of 2024, Brown took a position in Florida anyway. She was “slightly optimistic” about the passage of Florida Amendment 4, which would have overturned the restriction on abortions performed before fetal viability. Although it received nearly 58% of the vote later that fall, it failed to reach the 60% threshold required in Florida.

Brown admits some disappointment about not being able to work as a full-time specialist in complex family planning like her colleagues in California. Instead, she works 1 day a week in the local Planned Parenthood clinic and 1 day a week at her academic institution doing complex contraception visits and managing patients with early pregnancy loss. The rest of her week is spent doing routine Ob/Gyn care, where she doesn’t use the full spectrum of skills acquired in fellowship.

But Brown’s skillset is critical to the region. She often receives referrals from providers unwilling to jump through the regulatory hoops needed to perform an abortion on woman with a valid medical indication. “Frankly, a lot of physicians really just don’t have those skills of knowing how to do second trimester abortions or even second trimester procedures for fetal losses,” she said. For her, satisfaction comes from being able to provide care to the patient with a fetal demise who drove 5 hours from south Florida to her hospital, or the experience she can pass along to students and residents who would not have any exposure to the procedures they need to learn for many obstetric emergencies.

She knows that if she leaves Florida, many trainees won’t learn to provide emergency care that requires mastery of the procedures used to perform abortions. “I think just teaching them in general is probably what keeps me going,” said Brown.

Brown, Cansino, Colwill, Crebessa, Howard, and Steinauer reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A former pediatrician and disease detective, Ann Thomas is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon.

Admin_Adham

Admin_Adham